The initial buzz, controversy, and outcry over the emergence of Non-fungible Tokens, or NFTs, into the marketplace has created unprecedented interest in the technology. One may wonder where these art projects with blockchain-based proof of ownership may fall in the intellectual property space. To understand where NFT patent space is developing, it is important to first understand what an NFT actually is.

What is an NFT?

An NFT is a “non-fungible token,” meaning that it is a digital image with a unique digital signature ascribing ownership of the image to an individual entity. Thus, an NFT is a digital asset. This ownership is determined through code written in the Ethereum blockchain, a blockchain linked to the cryptocurrency Ethereum. Blockchain, which has other uses in the intellectual property space such as protecting trade secrets [link to trade secrets article], is here used to form a digital “lock” of sorts. An individual’s cryptocurrency “wallet,” which holds cryptocurrencies, will be able to hold a “key” of sorts to this lock, which thus will make the owner of the NFT the only person able to prove ownership of the NFT through the blockchain.

How are NFTs Profitable?

If this is confusing to you, don’t worry. Most people are in the exact same position, but that isn’t necessarily a problem if you want to understand the role of NFTs in the intellectual property space. As a new technology surrounded by controversy, whether it be from their negative environmental impact to the potential negative societal and economic impact such a volatile asset could have, there is a reason that NFTs are gaining popularity: their extreme volatility is viewed by some as a way to make a lot of money extremely quickly.

As an analogy, take trading cards. There is no intrinsic value in holding a valuable baseball card, except for the scarcity of the card and the fact that a collector wants that scarce asset. NFTs are similar, in that they are effectively unique pieces of digital art that are bought at a low “minting” price, but see their price skyrocket quickly due to a high number of potential buyers and a restricted number of copies of said NFTS. Thus, many celebrities, investors, companies, and individuals have made a lot of money by either minting NFTs or purchasing and flipping them for a higher price.

Early days for the NFT patent space

But how does this all relate to the patent space, you might ask? Any new technology opens up the potential for new patent territory to be staked out, and right now fewer than a hundred patents relating to NFTs have been granted or applied for. This small number of NFT patents leaves space open for companies to add to their intellectual property portfolio in this space. Not all cryptocurrency-related technologies have limited patent filings, however. Blockchain technology has over 100,000 patents related to it filed or applied for currently. This goes to show the potential of this technology in the intellectual property space to expand over the coming years.

While there is much potential to be had for NFTs in the intellectual property space, it is important to note that NFTs were not invented very recently. In fact, the oldest NFT patent was filed over twenty years ago: US7302703B2 filed by Google on Dec. 20, 2000. This patent is set to expire next year. However, many new patents will be laid open very soon in the 18-month publication window for patents following this expiration, which will likely lead to the patent space for NFTs growing very fast very soon.

Early Players in the NFT Patent Space

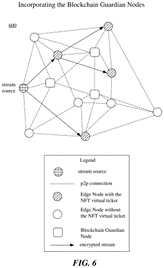

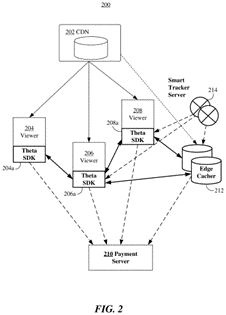

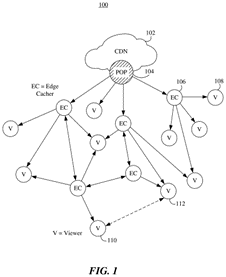

Theta Labs is an early player in the NFT Patent Space, but it’s important to note which patents are in the portfolios of companies such as Theta Labs. US11075891B1 (‘891) , or “Non-fungible token (NFT) based digital rights management in a decentralized data delivery network,” has a very long first claim with nearly 300 words, making it extremely narrow in scope. The problem with patents in the NFT space is that unless they are extremely broad, they are not especially defensible due to the fact that a slight deviation in code affecting a portion of one of the independent patent claims can make an effective reproduction of the patented invention a different invention under patent law. Some of the figures published with ‘891 are pictured below: if any tangential aspect of the patent was altered in a copycat invention, the copycat invention would not be affected by the patent.