Creating Real Value (Investors, Stock Market, M&A, Monetization) for Your Company through the Rapid Development of a Strategic Intellectual Property Portfolio

By John Cronin and Seth Cronin

Executive Summary

In order to challenge you as an executive or an investor of a small or early stage company looking to leverage your value to (1) raise money, (2) be acquired, (3) enhance your market value, or (4) increase revenue, we will discuss how to create real value (for investors, the stock market, M&A, or monetization) for your company through the rapid development of a strategic intellectual property portfolio. For more than twenty-one years, we have helped hundreds of small and early stage companies create real value, and we have benchmarked the rapid development of a strategic intellectual property portfolio to demonstrate significant value. Interestingly, over this time, we have seen few executives or investors who understand this, and worse, many do not believe it is possible to create real value using intellectual property (IP).

We have recognized the positive side of this topic that can give new hope for tired, low-growth companies, but we also recognize the existence of forces that directly impact whether or not a company takes advantage of rapid development of a strategic intellectual property portfolio. Finally, once this is understood, we can advise you on how to make real progress to gain leverage. We will discuss these topics in more detail.

- On the positive side, you will see that (1) your market has M&A value drivers related to patents, (2) you can begin to understand and take advantage of the ways investors value IP, and (3) there are unique monetization opportunities for early stage companies, such as IP asset-based lending.

- There are forces that impact IP portfolio development, such as (1) external forces, (2) internal forces, (3) how to use funding to successfully leverage IP, (4) you don’t think you have any potential IP, or (5) you are cost-conscious and think IP is too expensive.

- This all leads to insight on ways to make real progress, such as how to (1) leverage your IP when you lack the funding, (2) align with investors to secure funding, (3) understand the factors that determine whether your IP portfolio is weak and how to address these factors, and (4) understand how speed to the patent office plays a crucial role in portfolio development.

Does your market have M&A value drivers related to patents?

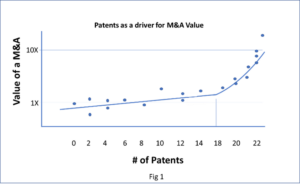

Over the years, we have seen that many early stage companies with the foresight to build a strong IP portfolio tend to benefit handsomely in an M&A transaction. The example data in Fig 1 represents spaces we have formally evaluated. There is strong rationale as to why there is a “hockey stick” pattern in portfolios with more than 18-20 patents. Our experience in the tech M&A market has shown several factors that would tell us why, after 18-20 patents, there are high multiples to the M&A value. Patents are valued by how they support sales, marketing, operating business, and innovative position. There are some market sectors in which the value of patents is an essential driver. Today, many markets have a convergence of technologies, and in these converged sectors, patents are incredibly valuable. There are many reasons why the “hockey stick” occurs at 18-20 patents:

Over the years, we have seen that many early stage companies with the foresight to build a strong IP portfolio tend to benefit handsomely in an M&A transaction. The example data in Fig 1 represents spaces we have formally evaluated. There is strong rationale as to why there is a “hockey stick” pattern in portfolios with more than 18-20 patents. Our experience in the tech M&A market has shown several factors that would tell us why, after 18-20 patents, there are high multiples to the M&A value. Patents are valued by how they support sales, marketing, operating business, and innovative position. There are some market sectors in which the value of patents is an essential driver. Today, many markets have a convergence of technologies, and in these converged sectors, patents are incredibly valuable. There are many reasons why the “hockey stick” occurs at 18-20 patents:

- It may be possible to easily conduct due diligence and invent around one or two patents, but as the portfolio grows, it becomes very difficult to do so. It is less believable that 18-20 patents can all be invented-around and devalued.

- A portfolio of 18-20 patents provides a sort of innovation prestige, as it shows that the seller believes in and has invested in protecting his or her inventions.

- A portfolio with 18-20 patents has a higher likelihood to fill the white spaces of the acquirer and, hence, appears as a better strategic fit.

- A portfolio with 18-20 patents means the competitors have far less of a position and further, that the acquirer is less motivated to shop around for another acquisition as the threat of litigation becomes a risk.

- A large patent portfolio is likely to show up in a large company’s competitive intelligence, particularly if the 18-20 patents are within a one-to-two-year time frame. Such a portfolio may convince acquirers to act sooner rather than later, as value may be significantly higher in another year or two.

- A strong portfolio of 18-20 patents adds security to the deal, as it’s less likely that freedom-to-operate issues will arise after the acquisition has closed.

Will you take advantage of raising your valuation in M&A by quickly developing a strong IP Portfolio?

Does your investor think IP is valuable?

Over the past twenty-one years, we have dealt with many investors. As shown in Fig 2, many investors’ belief in IP is based upon his or her experience (or lack thereof) in IP used in transactions of previous deals. Take, for example, the investor on the far right, who thinks IP has tremendous value and should be developed quickly and robustly. This investor likely made a very big hit on some deals where he or she saw IP creating high valuations, or large litigation wins, for example. Our investor on the other end of the spectrum just generically sees no value in IP. This could be for many reasons, such as the investor’s lack of experience in IP-related deals, or perhaps this investor believes value is created in other ways, such as building revenue growth. As you look across the spectrum, there are many different reasons investors have suggested as to why IP has value. However, it should be noted, that the investor on the far right could come into the same company as the investor on the far left, or vice versa.

Over the past twenty-one years, we have dealt with many investors. As shown in Fig 2, many investors’ belief in IP is based upon his or her experience (or lack thereof) in IP used in transactions of previous deals. Take, for example, the investor on the far right, who thinks IP has tremendous value and should be developed quickly and robustly. This investor likely made a very big hit on some deals where he or she saw IP creating high valuations, or large litigation wins, for example. Our investor on the other end of the spectrum just generically sees no value in IP. This could be for many reasons, such as the investor’s lack of experience in IP-related deals, or perhaps this investor believes value is created in other ways, such as building revenue growth. As you look across the spectrum, there are many different reasons investors have suggested as to why IP has value. However, it should be noted, that the investor on the far right could come into the same company as the investor on the far left, or vice versa.

This means that the company value is related to investors’ belief in IP and not the value of IP of the company. This, unfortunately, creates a paradigm for the executive team. The only way to shift the perspective of the investors on the left is with data, such as showing these investors the potential of the IP and the path to ROI.

Unique Monetization for early stage companies – IP Asset-Based-Lending

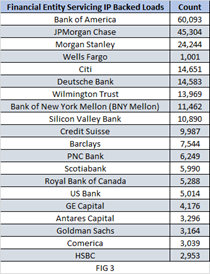

Asset-based lending (ABL) is a business loan secured by collateral (assets). For the present discussion, we will refer only to asset-based loans as a loan or a line of credit that is secured by patents. Having a large portfolio (i.e., greater than twenty patents) provides a much higher probability of the loan being approved. Typically, borrowers of an ABL want the loan to help the business grow; for example, they may desire the loan in order to fulfill a contract in place that needs working capital to perform. The patents are used to backstop the loan; in the event the loan is not repaid, the ABL lender will take the patents and monetize them to repay the loan. Therefore, the patents need to be of high quality and of a certain size and, ideally, have evidence of use of other violators to increase the probability of obtaining the loan. ABL markets are growing at the time of writing this, and there are more ABL lenders in the market than are shown in Fig 3. We are seeing the ABL terms appear to be better than standard loans and we have seen that ABL lenders are better partners since they conduct due diligence of the business and the IP (technology). Can you develop an IP portfolio to raise the probability and value of an ABL?

Asset-based lending (ABL) is a business loan secured by collateral (assets). For the present discussion, we will refer only to asset-based loans as a loan or a line of credit that is secured by patents. Having a large portfolio (i.e., greater than twenty patents) provides a much higher probability of the loan being approved. Typically, borrowers of an ABL want the loan to help the business grow; for example, they may desire the loan in order to fulfill a contract in place that needs working capital to perform. The patents are used to backstop the loan; in the event the loan is not repaid, the ABL lender will take the patents and monetize them to repay the loan. Therefore, the patents need to be of high quality and of a certain size and, ideally, have evidence of use of other violators to increase the probability of obtaining the loan. ABL markets are growing at the time of writing this, and there are more ABL lenders in the market than are shown in Fig 3. We are seeing the ABL terms appear to be better than standard loans and we have seen that ABL lenders are better partners since they conduct due diligence of the business and the IP (technology). Can you develop an IP portfolio to raise the probability and value of an ABL?

Are external forces driving you to develop an IP portfolio?

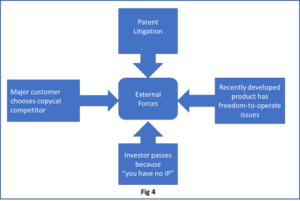

There are, without a doubt, strong external forces that can drive you to rapidly develop a strong IP portfolio. As shown in Fig 4, some of these external forces can be threatening to business. Suppose you lost a major customer to a competitor that copied your key features. In this case, no IP means no recourse. Suppose you are raising money and you just received notice of a patent lawsuit from a competitor. This blocks your raise until the patent suit is settled. One very frequent complaint we hear is that the company is about to release a new product and finds, through a freedom-to-operate opinion, that a competitor’s patent stands directly in the path of its new product that took several years to develop. Finally, a scenario we are called on frequently to help fix is a situation where the CEO finds that even after receiving a Letter of Interest for a fundraise, he is stopped from proceeding to the next stages, as investor diligence shows no IP, which may be a requirement of the investor. These are just a few of the external forces that can drive a company to develop a portfolio, but many times, when it comes to these examples, it’s too late. Will you wait until it’s too late?

There are, without a doubt, strong external forces that can drive you to rapidly develop a strong IP portfolio. As shown in Fig 4, some of these external forces can be threatening to business. Suppose you lost a major customer to a competitor that copied your key features. In this case, no IP means no recourse. Suppose you are raising money and you just received notice of a patent lawsuit from a competitor. This blocks your raise until the patent suit is settled. One very frequent complaint we hear is that the company is about to release a new product and finds, through a freedom-to-operate opinion, that a competitor’s patent stands directly in the path of its new product that took several years to develop. Finally, a scenario we are called on frequently to help fix is a situation where the CEO finds that even after receiving a Letter of Interest for a fundraise, he is stopped from proceeding to the next stages, as investor diligence shows no IP, which may be a requirement of the investor. These are just a few of the external forces that can drive a company to develop a portfolio, but many times, when it comes to these examples, it’s too late. Will you wait until it’s too late?

Are internal forces driving you to develop an IP portfolio?

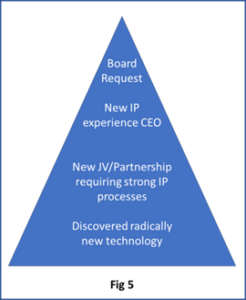

A corollary to the external forces discussed previously are the strong internal forces that can drive you to rapidly develop a strong IP portfolio. Many times, a company discovers a new direction that is overwhelmingly better than its existing direction; everyone gets excited but then realizes the company needs to obtain IP coverage immediately. Sometimes a company may find that it must leverage a new JV/partnership with an aggressive IP rights section of the agreement, forcing it to develop an immediate and strong IP process to get the IP portfolio in shape. A very common change within a company is the hiring of a new executive (CEO/CTO) with previous experience in leveraging IP, where the executive starts to drive a new IP program. Finally, a very important internal force is when a new board member with IP experience is brought on and recognizes the company needs to develop an IP portfolio quickly.

A corollary to the external forces discussed previously are the strong internal forces that can drive you to rapidly develop a strong IP portfolio. Many times, a company discovers a new direction that is overwhelmingly better than its existing direction; everyone gets excited but then realizes the company needs to obtain IP coverage immediately. Sometimes a company may find that it must leverage a new JV/partnership with an aggressive IP rights section of the agreement, forcing it to develop an immediate and strong IP process to get the IP portfolio in shape. A very common change within a company is the hiring of a new executive (CEO/CTO) with previous experience in leveraging IP, where the executive starts to drive a new IP program. Finally, a very important internal force is when a new board member with IP experience is brought on and recognizes the company needs to develop an IP portfolio quickly.

Wherever the need comes from, an internal force wins out over the older forces that made IP less of a priority. The same company with a strong internal force pivots to make IP a key value driver in its future. Unfortunately, what this means is that there were years of value created that wasn’t captured. Will you wait for an internal force to wake you up to create value with your IP position?

You have the funding, but you will still fall behind!

Why do innovators that have the funding still fail to take the time for internal documentation processes and the patent office requirements? The problem is emphasized for smaller and early stage companies where there is a lot of innovative capacity, but little expertise or time to get a solid IP portfolio built. With a long list of to-dos that may include everything from managing technical teams, researching competitors, and interviewing potential new hires to quality testing prototypes, negotiating contracts with vendors, or fine-tuning business plans for investors, when does the time come to sit down and (1) understand the issues facing the business, (2) visualize what the IP landscape looks like, (3) understand the white space opportunities available, and (4) create a list of patentable inventions, draft figures, and articulate claim language? The answer, based on the conversations we’ve had with hundreds of companies is, likely, never. Worse, when the time finally comes to submit even a single patent application, the inventions patented are usually anything but strategic. Typically, such applications only cover the most recent product going out the door, instead of where the company is headed. With so many competing, urgent responsibilities, key innovators will only find the capacity to document top-of-mind ideas in a very “ad hoc” fashion, leaving the high future value, speculative technologies to languish until another day that may never come. This, of course, only considers the patent process. Other equally valuable, though less urgent, types intellectual property (IP), such as trade secrets and enabled publications, may be pushed even further towards the backburner of a company’s invention pipeline. Can you leverage your funding to ensure you don’t fall behind?

Why do innovators that have the funding still fail to take the time for internal documentation processes and the patent office requirements? The problem is emphasized for smaller and early stage companies where there is a lot of innovative capacity, but little expertise or time to get a solid IP portfolio built. With a long list of to-dos that may include everything from managing technical teams, researching competitors, and interviewing potential new hires to quality testing prototypes, negotiating contracts with vendors, or fine-tuning business plans for investors, when does the time come to sit down and (1) understand the issues facing the business, (2) visualize what the IP landscape looks like, (3) understand the white space opportunities available, and (4) create a list of patentable inventions, draft figures, and articulate claim language? The answer, based on the conversations we’ve had with hundreds of companies is, likely, never. Worse, when the time finally comes to submit even a single patent application, the inventions patented are usually anything but strategic. Typically, such applications only cover the most recent product going out the door, instead of where the company is headed. With so many competing, urgent responsibilities, key innovators will only find the capacity to document top-of-mind ideas in a very “ad hoc” fashion, leaving the high future value, speculative technologies to languish until another day that may never come. This, of course, only considers the patent process. Other equally valuable, though less urgent, types intellectual property (IP), such as trade secrets and enabled publications, may be pushed even further towards the backburner of a company’s invention pipeline. Can you leverage your funding to ensure you don’t fall behind?

So, you don’t think you have any IP?

There are a large group of executives that believe they really do not have IP in their company. This is a fundamental mistake. In the many companies to which we are routinely introduced, we have yet to find one that does not have IP. We have worked in many technology areas, from food to aerospace; we have seen time and again that if you have folks working on solving problems in business, in technology, you’re likely developing IP. If you have certain ways you do things that you wouldn’t want competitors to find out about, that’s IP, likely in the form of trade secrets. If you have ideas that you are improving, but don’t think it is financially worth it to file patents, that’s IP in the form of enabled publications, that when published, provide you with freedom-to-operate, but more importantly, stop another company from patenting it and suing you. When you look at ideas and feel they are “obvious,” well, that’s a problem. The layman’s definition of “obvious” is not the legal definition of “obviousness.” You make a classic error by thinking the ideas generated by your team are obvious.

There are a large group of executives that believe they really do not have IP in their company. This is a fundamental mistake. In the many companies to which we are routinely introduced, we have yet to find one that does not have IP. We have worked in many technology areas, from food to aerospace; we have seen time and again that if you have folks working on solving problems in business, in technology, you’re likely developing IP. If you have certain ways you do things that you wouldn’t want competitors to find out about, that’s IP, likely in the form of trade secrets. If you have ideas that you are improving, but don’t think it is financially worth it to file patents, that’s IP in the form of enabled publications, that when published, provide you with freedom-to-operate, but more importantly, stop another company from patenting it and suing you. When you look at ideas and feel they are “obvious,” well, that’s a problem. The layman’s definition of “obvious” is not the legal definition of “obviousness.” You make a classic error by thinking the ideas generated by your team are obvious.

One of the most powerful patents IBM ever filed was a “cursor” invention, where the computer’s cursor changed its shape based on the function the computer was in (exemplified as the blinking line which changed to a blinking insert block in a word processor). Fortunately, IBM patented the invention (instead of assuming it was obvious) and since you couldn’t make a computer work without it, leveraged an industry. You may be thinking there is no IP in the company because none of the technical people are requesting to file patents; again, this is a problem, as most technical people, even the ones who have had patents, do not like the work involved to get a patent, usual work that must be done on their own time. You may think you don’t have IP because you have never been hurt by not having it. That’s like saying since I haven’t had a heart attack, I won’t keep myself in shape. You may find that you sell your company for the standard 1.2X revenue multiplier, never knowing IP could change that by 5X-10X. What if the acquirer was very motivated by IP? With no IP, you would have little to no value. What if investors want IP? Well, because you didn’t invest in it, you are likely to miss the investment from that investor. Or, perhaps, try getting sued for patent infringement and having no IP trading cards with which to fight back. How about a competitor that decides to copy your product? No IP means no pushback. How about an employee that decides to leave and start his own company doing what you do? No trade secret program means likely no teeth in a trade secret theft litigation. So, do you really think you have no IP, or are you convincing yourself you don’t have IP?

You are incredibly cost-conscious, is IP too expensive?

Many executives tend to spend their time concerned with the important expense side of the business. In the disciplined mindset of preserving cash, it makes sense to consider IP matters as an expense. However, there are many times when being cost-conscious is taken too far. Consider a young person keeping their costs low to extend a low salary as far as possible. Wouldn’t any parent recommend that the young person save something, even contributing to building their 401K as an asset? Over time, small investments can add up, generating enormous value. Likewise, intellectual property investment is an asset savings program. Without this, a company has no investment in the assets that clearly are worth a large percentage of the company. In today’s market, 80% of a company’s value is held in intangibles assets, and it’s likely that 50% of these intangibles are related to IP (e.g., trade secrets, patents, etc.) There are many instances where cost cuttings just really go too far. Many CEOs with whom we have worked have come to the long-term view that no matter what the cost pressures on the company, the company has no future without investment in its IP. Will you let the cost management mindset eliminate the company’s future value?

Many executives tend to spend their time concerned with the important expense side of the business. In the disciplined mindset of preserving cash, it makes sense to consider IP matters as an expense. However, there are many times when being cost-conscious is taken too far. Consider a young person keeping their costs low to extend a low salary as far as possible. Wouldn’t any parent recommend that the young person save something, even contributing to building their 401K as an asset? Over time, small investments can add up, generating enormous value. Likewise, intellectual property investment is an asset savings program. Without this, a company has no investment in the assets that clearly are worth a large percentage of the company. In today’s market, 80% of a company’s value is held in intangibles assets, and it’s likely that 50% of these intangibles are related to IP (e.g., trade secrets, patents, etc.) There are many instances where cost cuttings just really go too far. Many CEOs with whom we have worked have come to the long-term view that no matter what the cost pressures on the company, the company has no future without investment in its IP. Will you let the cost management mindset eliminate the company’s future value?

You do not have the funding to create and then leverage your IP and protect your future!

When innovators do not have the funding to adequately create and then to leverage the company’s IP, it is usually because the company isn’t aware of the opportunities others have found to use patents to get new funding. Here are a few of the opportunities we see:

When innovators do not have the funding to adequately create and then to leverage the company’s IP, it is usually because the company isn’t aware of the opportunities others have found to use patents to get new funding. Here are a few of the opportunities we see:

Opportunity 1: Develop and leverage a list of ideas. First, as the old adage goes, ‘it takes money to make money.’ However, it only takes a little money to develop a plan that investors are likely to fund. You don’t need patents or even provisional applications filed. But if instead you created a landscape or framework that describes the R&D, technology, and product areas, then identified the many valuable ideas (i.e., potential patents) that the investment could fund, you would have a compelling story for investors. As we discussed above, when you find the right investors who believe in IP, it’s simple to align with their interests.

Opportunity 2: Develop a trade secret program. Trade secrets are powerful and very inexpensive to capture and leverage. Many early stage companies do not have a practical trade secret process, nor have they systematically identified their trade secrets. By installing a trade secret process and trade secret registry, the company tremendously reduces the risk that its competition will gain access to valuable business processes and knowhow. Moreover, a trade secret process and registry can show the innovativeness of the company. This story can be told to investors who may be sitting on the sidelines because they see too much risk or don’t think the company is innovative.

Opportunity 3: Use enabled publications as low cost, “poison the well” strategy. Enabled publications are very inexpensive and powerful, but your patent attorney is not likely to ever propose this strategy as he is risk-adverse and would rather see patent protection. Enabled publications create prior art to stop others from patenting your technology. When you don’t have a lot of funding, publications become a strong tool to use by patenting a few areas and publishing all the improvements.

Opportunity 4: Let the next raise pay for patents, you pay for provisional applications. A key low-cost strategy is to file low-cost provisional patent applications. This will show innovation but let the next fundraise pay for the filing of the full patent applications. In this way, the use of funds is low, the innovation is secured, and the investors have another reason to invest in the next round.

How Speed to the Patent Office plays a crucial role in portfolio development

The first reason for the need for speed includes some recent fundamental changes in the USPTO’s regulatory framework which have contributed to the need for rapidity in a patent filing strategy. The first aspect of the is the “first-to-file” rule versus the “first-to-invent” rule, so the need to get to the patent office is important. Are you reacting quickly enough?

The first reason for the need for speed includes some recent fundamental changes in the USPTO’s regulatory framework which have contributed to the need for rapidity in a patent filing strategy. The first aspect of the is the “first-to-file” rule versus the “first-to-invent” rule, so the need to get to the patent office is important. Are you reacting quickly enough?

The second reason for speed is to deal with the increasing speed of innovation, which can be seen nowhere more clearly than through the growth of patent filings in recent years. Although it took 155 years for the United States to issue the first five million patents, the next five million were granted in the succeeding twenty-seven years. Exponential technology development of this kind spans and connects each sector of the economy, changing behaviors and modifying culture from the foosball tables of Silicon Valley startups to the board rooms of Fortune 500 companies. Now more than ever, the race to the patent office is one the that requires speed, strategy, and tenacity. The race to the patent office has been further exacerbated by the transition to a first-inventor-to-file (FITF) system from a first-to-invent (FTI) system which became effective on March 16, 2013 (USPTO, 2016). The next ten million U.S. patents are already being sketched on the literal and figurative whiteboards across the world, poised to protect and elevate that status of proactive, expedient inventors, all while discouraging and excluding reactionary procrastinators. Are you ready to participate in the race to the patent office?